Did you know that, if things had gone differently, the Pompidou Centre could have been an egg? In the 1969 competition for the Paris art centre – ultimately won by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, with their inside-out symphony of pipework – a radical French architect called André Bruyère submitted a proposal for a gigantic ovoid tower. His bulbous building would have risen 100 metres above the city’s streets, clad in shimmering scales of alabaster, glass and concrete, its walls swelling out in a curvaceous riposte to the tyranny of the straight line.

“Time,” Bruyère declared, “instead of being linear, like the straight streets and vertical skyscrapers, will become oval, in tune with the egg.” His hallowed Oeuf would be held aloft on three chunky legs, while a monorail would pierce the facade and circle through the structure along a sinuous floating ribbon. The atrium was to take the form of an enclosed globe, like a yolk.

Baghdad would have been Frank Lloyd Wright’s grandest project by far – had the king not been assassinated in a coup

“Between the hard geometries,” Bruyère added, “comes the sweetness of a volume [with] curves in all directions, in contrast to these facades where the angle always falls right from the sky, always similar. So, the egg.” Sadly, it wasn’t to be. His ovular poetry didn’t impress the judges and Paris got its high-tech hymn to plumbing instead.

L’Oeuf de Pompidou is one of many astonishing schemes to feature in Atlas of Never Built Architecture, a bulging compendium of dashed hopes and broken dreams that charts a fascinating alternative universe of “what ifs”. It is a world of runners-up and second bests, an encyclopaedia of hubristic plans that were too big, expensive or weird to make it off the drawing board.

Cracking idea … André Bruyère’s mega egg and Pompidou rival. Photograph: © Bruyère Fund. SIAF/City of Architecture and Heritage/Archives of Contemporary Architecture

It features best laid plans that became victims of political coups and economic crises, alongside the megalomaniacal visions of toppled tyrants, and projects that were scuppered by budget shortfalls, natural disasters and even a plane crash. It is a calamitous catalogue of corruption, bankruptcy and death, as well as a memorial to the untold hours of wasted work and unpaid labour that architects endure. But it all makes for a highly entertaining romp through what the world might have looked like, had fate chosen a different path.

One spread depicts a fantastical vision of a pleasure island, where a needle-thin spire rises from the cone-shaped dome of an ornate pavilion, surrounded by lush gardens dotted with more glass domes. The central building is raised on a platform and engulfed by a reflecting pool, reached by a majestic spiral ramp, recalling the processional route to an ancient ziggurat. It looks like the glitzy dream of a wealthy desert petro-state. And it is – except that it’s not the work of a contemporary “starchitect” for the Gulf, but the vision of Frank Lloyd Wright, drawn up in 1957 for Baghdad.

Schöffer described his skyscraping smartphone tower as ‘an intense living flame, constantly transforming’

Wright had been invited by King Faisal II to design an opera house for the city, alongside a range of other stars of the day, including Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, Gio Ponti and Walter Gropius, who had been commissioned to design universities, government buildings, sports complexes and other palaces of culture. On his descent into the airport, Wright noticed a long, thin island in the Tigris River – a location he thought preferable to the downtown site he had been allotted. “The island, Mr Wright, is yours,” replied the king.

As was his habit, Wright quickly expanded his brief, concocting an entire Plan for Greater Baghdad, which he dubbed Edena. Along with the opera house, there would be a civic auditorium, a planetarium, art museums, a grand bazaar, gardens, fountains and tiered highways, all wrought in the curving language of caliph-era Baghdad, known as the Round City, when it was surrounded by concentric circular walls. It would have been Wright’s grandest project by far – if the king had not been assassinated in a coup in 1958. The architect himself died the following year, aged 91.

A multimedia answer to the Eiffel Tower … Nicolas Schoffer’s blaring cybernetic skyscraper. Photograph: Nicolas Schoffer

The book’s two authors, Los Angeles-based architecture writers Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, have foraged far and wide to compile a collection with impressive geographic scope and depth, beyond the usual suspects. Their research led to a “shortlist” of 5,000 projects, which they distilled to 1,000, then cut to 350 for the book – one of Phaidon’s hefty atlas tomes, weighing in at 1.5kg, with a £100 price tag.

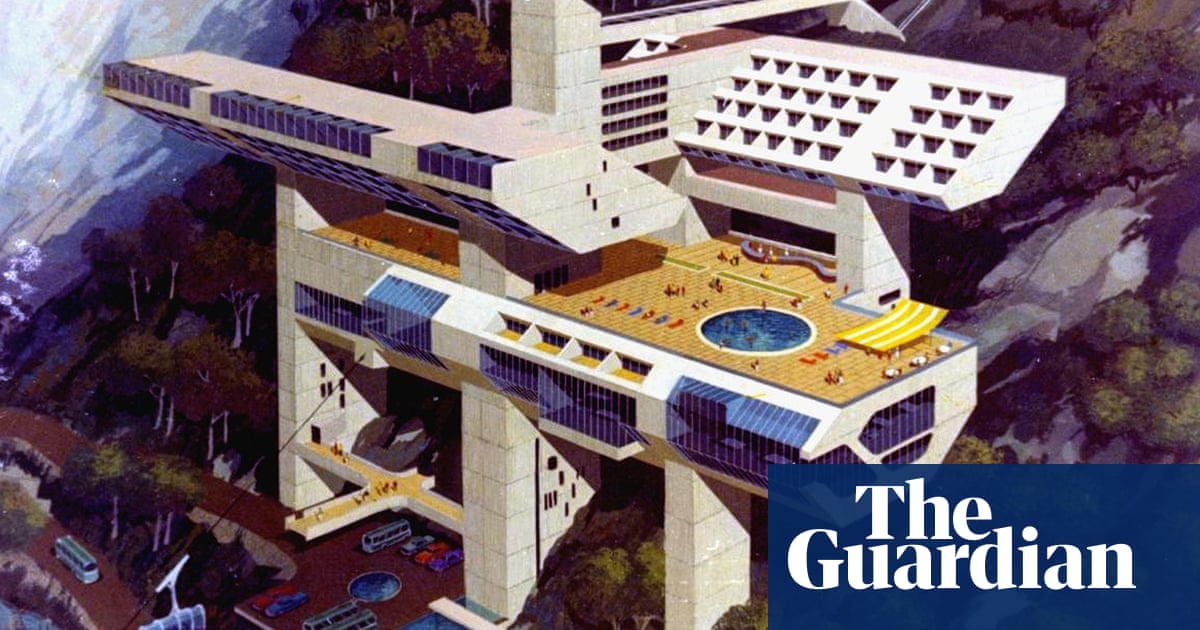

The projects range from bold parliaments for African cities, to a futuristic hotel that would have hovered above Machu Picchu, as well as what the South Bank of the Thames might have looked like if the American PoMo doyen Philip Johnson had had his way (Answer: a cartoonish neo-brutalist fantasy of the Palace of Westminster, teeming with crenelated towers.) There are plenty of plans that didn’t materialise the first time around, but later realised elsewhere, as well as ideas that were far ahead of their time, but now prove to be unnervingly prescient.

One was Hungarian-French artist Nicolas Schöffer’s Tour Lumière Cybernétique. This illuminated beacon would have been an interactive multimedia answer to the Eiffel Tower, a skyscraper-sized smartphone designed to broadcast a barrage of notifications across the skyline. Bristling with arrays of loudspeakers, flashing lights, smoke signals, moving rods, rotating mirrors and more than 5,000 projectors, the tower was designed to relay data concerning the weather, traffic, news and even citizens’ movements.

skip past newsletter promotion

Original, sustainable ideas and reflection from designers and crafters, plus clever, beautiful products for smarter living

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. Utilizamos Google reCaptcha para proteger nuestro sitio web y se aplican la Política de Privacidad y Términos de Servicio de Google.

después de la promoción del boletín

Robert Young dijo que no construir sobre Grand Central era como poseer “tierras por valor de $100 mil millones y nunca ararlas”

Schöffer lo describió como “una llama viva intensa, constantemente transformada y transformable”. Él veía su faro como una forma de democratizar la información, que, según él, de lo contrario estaría limitada a quienes controlan el gobierno y la producción. Pero en la década de 1970, las posibilidades de la cibernética comenzaron a ser vistas cada vez más como una amenaza, consideradas como herramientas que permitirían la invasión de la privacidad y limitar las libertades personales. La torre de Schöffer quizás no se materializó, pero sus principios perduran en los centros de recolección de datos de las “ciudades inteligentes”, menos visibles en vallas publicitarias que ocultas en anónimos centros de datos.

Las torres aparecen a lo largo del libro, este tipo de edificio tan ambicioso es el más propenso a fracasar, y a menudo desencadenan consecuencias no deseadas. La resistencia del querido Terminal de Grand Central en Nueva York, por ejemplo, se debe en parte a la reacción provocada por un plan en 1954 para reemplazarlo por un rascacielos circular de 109 pisos. El diseño en forma de reloj de arena, del arquitecto chino-estadounidense IM Pei, fue encargado por Robert Young, entonces presidente de la moribunda New York City Railroad, quien pensaba que no aprovechar los derechos aéreos sobre la estación histórica era tan insensato como poseer “un terreno por valor de $100 mil millones y nunca ararlo”.

Ecos del Parlamento… Las torres almenadas de Philip Johnson propuestas para la orilla sur del Támesis. Fotografía: Ned Paynter/Friends of San Diego Architecture

El proyecto de Pei, apodado el Hiperboloide debido a su forma retorcida, habría sido el edificio más alto y costoso del mundo en ese momento. Pero, enfrentando ganancias en picada y una investigación del Senado sobre el declive de la industria, Young se suicidó en 1958, acabando con cualquier esperanza para la torre. Mientras tanto, la oposición a los planes ayudó a impulsar el movimiento moderno de preservación, otorgando al amado terminal el estatus de monumento en 1967.

Aunque la torre de Pei podría haber ofrecido vistas espectaculares de Manhattan, lo mismo probablemente no se podría decir de la Torre de Indiana, ideada por César Pelli en 1981. El arquitecto nacido en Argentina, quien luego diseñaría las icónicas Torres Petronas de Kuala Lumpur, fue llamado para crear un hito para Indianápolis que rivalizara con el Arco Gateway de San Luis o la Aguja Espacial de Seattle. Su solución fue un obelisco de 228 metros de altura de concreto y piedra caliza, con un paseo de 2.8 km que se espiralaba hasta la cima, donde los visitantes podían contemplar los extensos campos de cultivo de Indiana. “Como la Torre Eiffel en Europa, será la cosa que debes ver”, afirmaba Pelli. “¡Será conocida tanto en Moscú como en Singapur!”

Si vas a hacer algo malo, no lo hagas grande

Los lugareños no estaban tan impresionados. Algunos pensaron que se parecía demasiado a una mazorca de maíz, afianzando el estereotipo de Indiana como un lugar rural atrasado. Otros lo compararon con una torre de extracción de petróleo, mientras que un juez de apelaciones dijo que parecía un manojo de alambre de gallinero. “Si vas a hacer algo malo”, dijo el presidente de la sociedad local de arquitectos, “no lo hagas grande”.

Los consultores externos contratados para evaluar la viabilidad del proyecto fueron igualmente francos. “Estructuras en las que puedes subir y mirar funcionan en ciudades como Seattle”, escribieron, “donde hay dos cadenas montañosas y el Estrecho de Puget, pero puede que no sea atractivo en una ubicación del medio oeste simplemente porque no hay tanto que ver cuando llegas allí arriba”.

El maestro italiano Carlo Scarpa era sereno acerca de sus numerosos planes no realizados. No construir era posiblemente la única forma de garantizar la paz. “Es mejor no hacer nada”, dijo, discutiendo su Teatro Cívico no construido para Vicenza. “Así todos estarán contentos: el consejo municipal, porque ha evitado las críticas que pueden dirigirse a aquellos que hacen algo… la oposición, porque puede decir que la administración no hace nada, después de haber anunciado el teatro; aquellos que no quieren el teatro, porque no estará ahí; aquellos que lo desean, porque pueden seguir quejándose de que no hay teatro; mientras tanto, soñando, cada uno por su cuenta, con un teatro ideal, hecho a su imagen y semejanza”.

A veces, el proyecto perfecto es mejor dejarlo en la imaginación.

Atlas de Arquitectura Nunca Construida se publica por Phaidon el 22 de mayo de 2024, £100